Addressing systemic injustice in the criminal justice system

Yoorrook heard evidence of the critical issues that need addressing in Victoria’s criminal justice system, including overt structural racism.

You can read more about the specific issues raised with Yoorrook in Chapters 9 to 14 of the full report.

“I believe the system is riddled with racism; the system focuses on punishment and not rehabilitation; and the system needs to change.”

– Aunty Jill Gallagher AO

Evidence before Yoorrook shows that:

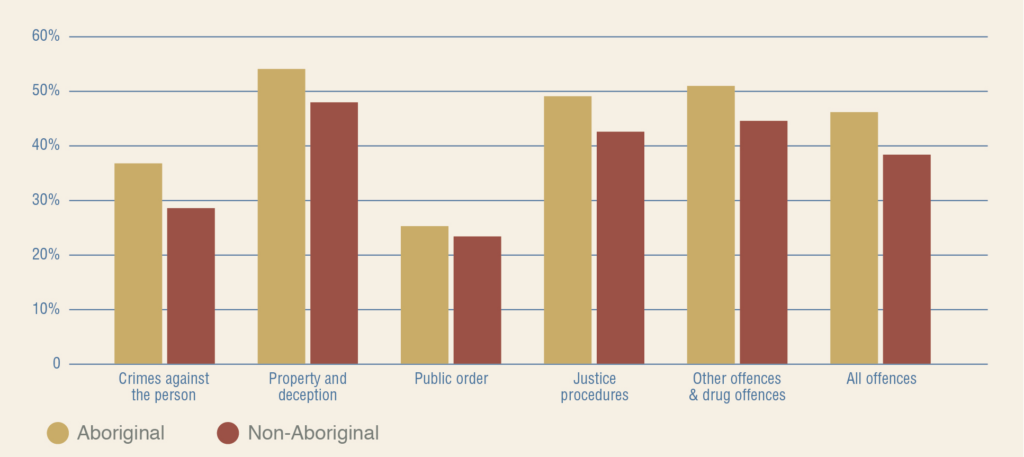

- First Peoples are subject to racial profiling and over-policing

- cultural awareness training for police is inadequate and, in the case of recruit training, contains offensive content

- police are less likely to issue cautions and recommend diversion for Aboriginal people

Arrest as outcome of alleged offender incident, year ending December 2022

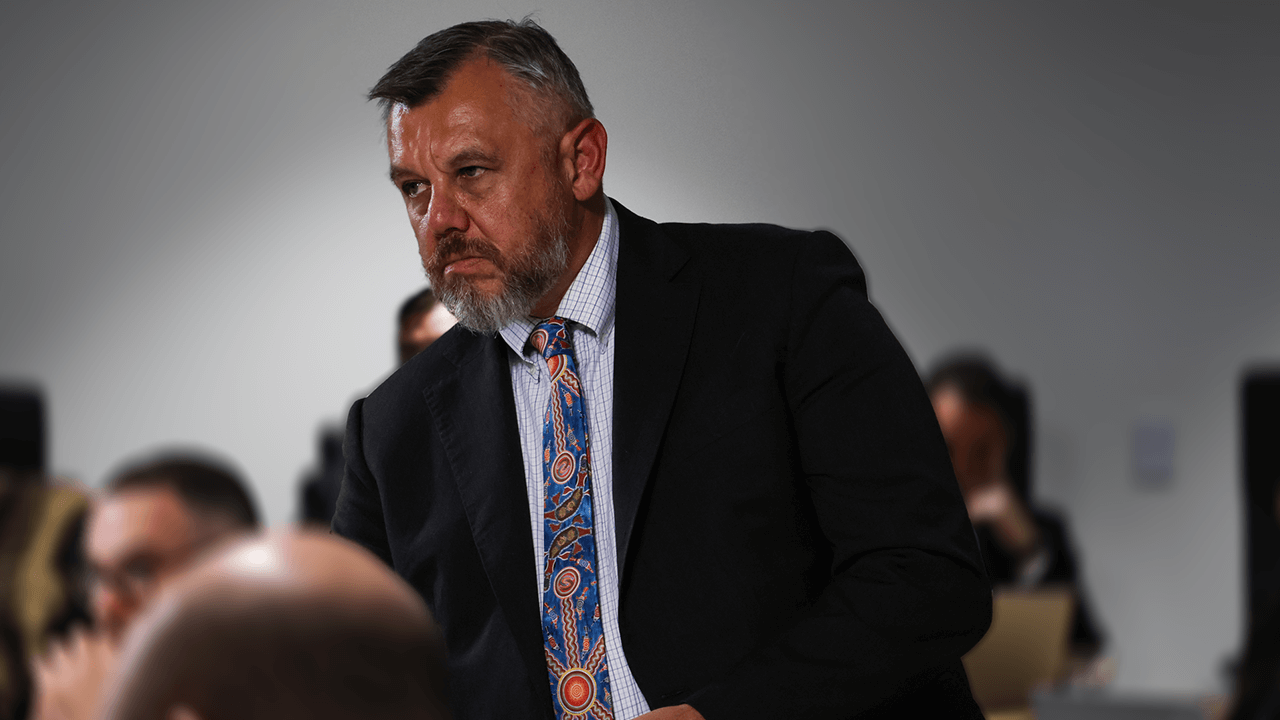

Yoorrook Senior Counsel Assisting and proud Wirdi man Tony McAvoy SC questioned Victoria’s Minister for Police, the Hon. Anthony Carbines MP, in hearings about injustices experienced by First Peoples at the hands of police.

Minister Carbines accepted that, for many Aboriginal people, their experience of policing is one in which they are the subject of racial profiling and other injustice.

Yoorrook heard that Victoria’s police complaints system is failing First Peoples. The system routinely denies or justifies police misconduct and fails to hold officers or management to account. The vast majority of complaints about police are investigated by police which undermines effectiveness and generates mistrust. There is compelling evidence for the need of a truly independent police complaints system.

Yoorrook received evidence about the long overdue decriminalisation of public drunkenness that will occur in November 2023. Evidence was heard about the need for independent evaluation to ensure that police do not use other existing powers to detain intoxicated people after the public drunkenness offence is repealed.

Yoorrook heard evidence about a serious gap in the protection offered by Victoria’s anti-discrimination laws, meaning that if a police or prison officer mistreats someone because of their race, the person is unlikely to be able to bring a racial discrimination complaint in the Victorian jurisdiction. Yoorrook was also advised of ways this problem has been fixed in other Australian jurisdictions.

Children and young people involved in the criminal justice system are particularly vulnerable and face multiple forms of disadvantage. This includes being victims of abuse, trauma, neglect or family violence, having a history of substance abuse, having cognitive difficulties and mental health issues and being disengaged from education. Yoorrook heard that this reinforces the need for justice responses that help children and young people instead of harsh, punitive responses that are likely to lead to greater criminal justice involvement.

“[O]ne of the things, I think, that’s particularly successful about that service [the Aboriginal Youth Justice Program] is the continuity of care that it provides, the place-based response. So Aboriginal young people having Aboriginal workers that are there to walk alongside them from that first point of contact with the system, but also Aboriginal workers who can remain with them, no matter where their trajectory heads, so that if a young person becomes involved in the system, that they’re not having to go through changes of workers and the like, which we know can be disruptive to the gains they’re making.”

– Youth Justice Commissioner Andrea Davidson

Yoorrook received evidence about ongoing problems with the over-representation of First Peoples children and young people in the youth justice system but heard that there has been recent success in reducing this rate and that the Victorian Government has a goal of zero involvement.

Yoorrook also heard about the need for improved cautioning and diversion programs for First Peoples children and young people, and the need to stop harmful conditions in youth prisons including the use of solitary confinement.

There is an urgent need to raise the age of criminal responsibility to at least 14. Victoria’s laws allow children as young as 10 to be arrested, charged, prosecuted and imprisoned. The Victorian Government has committed to raise the age to 12 within the next year and to 14 by 2027. Yoorrook heard that this is too slow.

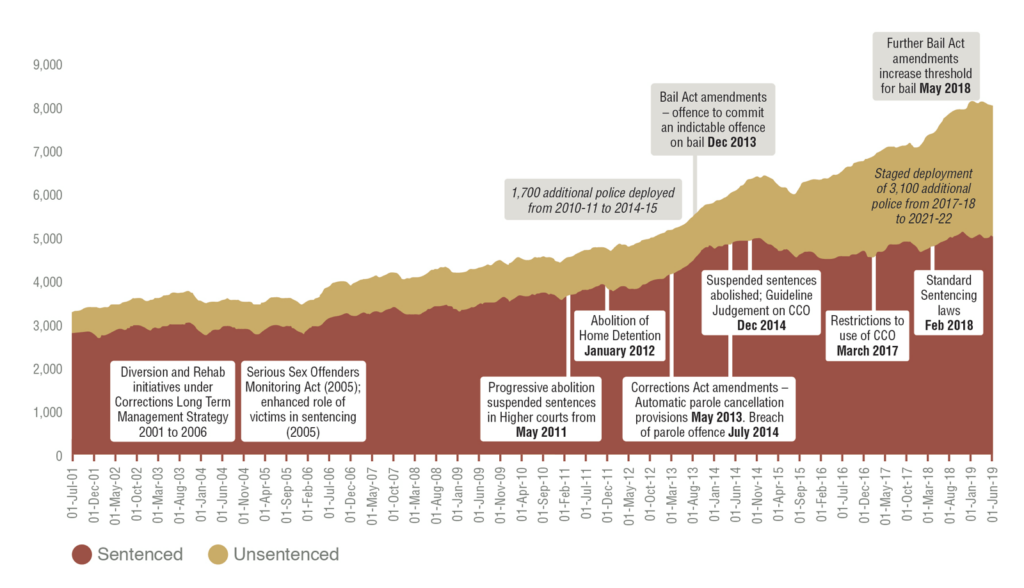

Punitive changes to Victoria’s bail laws in 2013 and 2018 led to a dramatic rise in the number of First Peoples imprisoned on remand, waiting for their trial or sentence. Yoorrook heard that Aboriginal women were hardest hit by these changes and were often denied bail and imprisoned for repeat low level non-violent offending. Yoorrook received evidence that government ignored the concerns and advice of First Peoples about the inevitable impact of its bail reforms, making a mockery of government commitments to self-determination and reducing over-imprisonment and eroding the trust that had been generated through the justice-related forums established to listen to and consult with Aboriginal people.

The chart below shows the correlation between policy and legislative changes, and increased numbers of people in custody over the ten years to 2019. As can be seen, these legal changes have led to increases in Victoria’s prison population. These changes have had a disproportionate effect on First Peoples.

What eventuated was a stark reminder that the State retains power and control over the fate of First Peoples, even when it adopts the language of ‘partnership’, ‘working together’, ‘respect’ and ‘self-determination’. It highlights why treaty is so critical to realising First Peoples’ fundamental right to self-determination. Yoorrook heard that the government is now willing to wind back many of the punitive changes it made and that legislation to do this is imminent.

Yoorrook received evidence about the need for sentencing reforms to reduce the rate of imprisonment of First Peoples. This included reforms to take into account the unique systemic and individual background factors affecting First Peoples. Mandatory sentencing laws which limit the ability of courts to ensure that each sentence is fair and appropriate need to be repealed.

Yoorrook heard evidence about failures in Victoria’s prison system including:

- systemic failures in prison health care

- lack of cultural connection and programs

- poor access to rehabilitation programs

- cruel, inhuman and degrading treatment in prison through the use of solitary confinement and strip searching

- barriers to reporting abuse and misconduct

- lack of independent oversight

- non-compliance with human and cultural rights obligations

- non-compliance with inspection processes that Australia has agreed to under an international treaty

Yoorrook also received evidence about problems accessing parole. Parole is the system that allows some people to be released from prison into the community under supervision after they have served their minimum term of imprisonment. The best evidence is that supervised and supported release on parole reduces the risk that someone will reoffend. As a result of reforms in 2013 which made it harder to get parole, the number of people accessing parole has fallen significantly. First Peoples are less likely to be granted parole. This denies them the benefits of parole, increases the risk of reoffending and contributes to over-imprisonment, as more First Peoples will be in prison for longer.

Finally, Yoorrook heard evidence about the acute and ongoing pain and trauma of deaths in custody for First Peoples. First Peoples are dying at higher rates in custody not because they are more likely to die once they are in custody, but because of the staggering rates at which governments are arresting and jailing Aboriginal people. Evidence shows that the key to reducing First Peoples deaths in custody is reducing the rate at which they are put in custody by police, courts and governments.

Read more about what need to change in the criminal justice system in the full report.