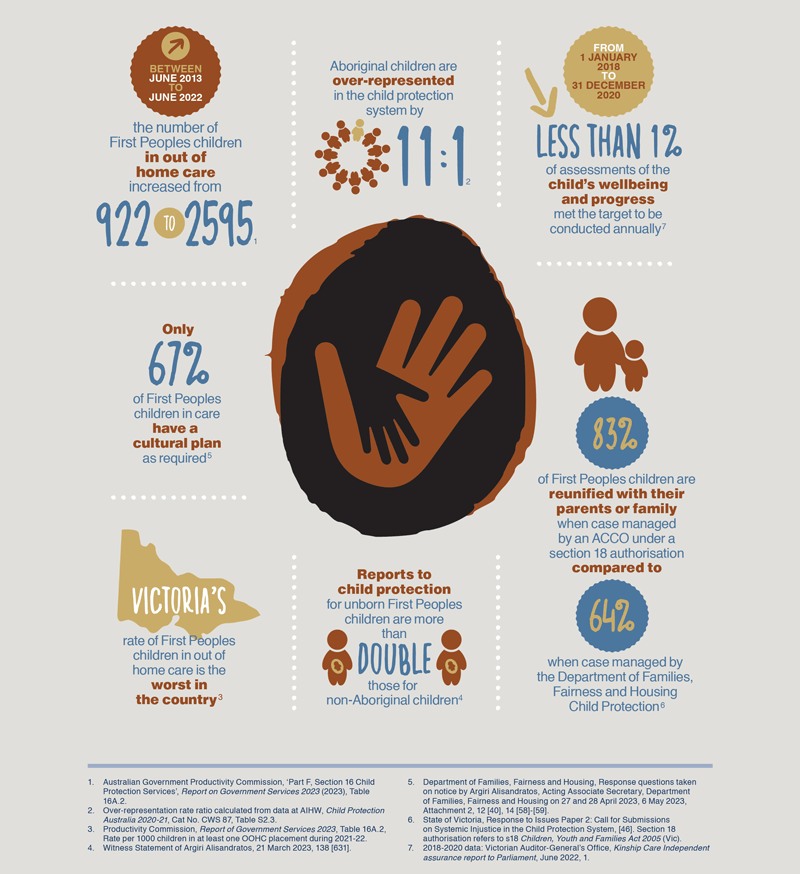

Addressing systemic injustice in the child protection system

Yoorrook heard evidence of the critical issues that need addressing in Victoria’s child protection system.

You can read more about the specific issues raised with Yoorrook in Chapters 4 to 8 of the full report.

What Yoorrook heard:

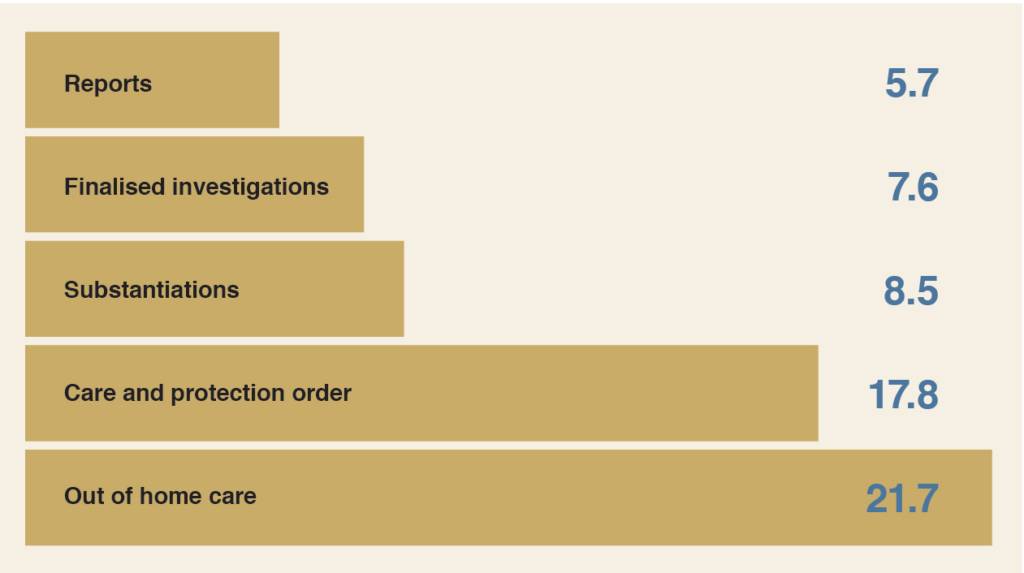

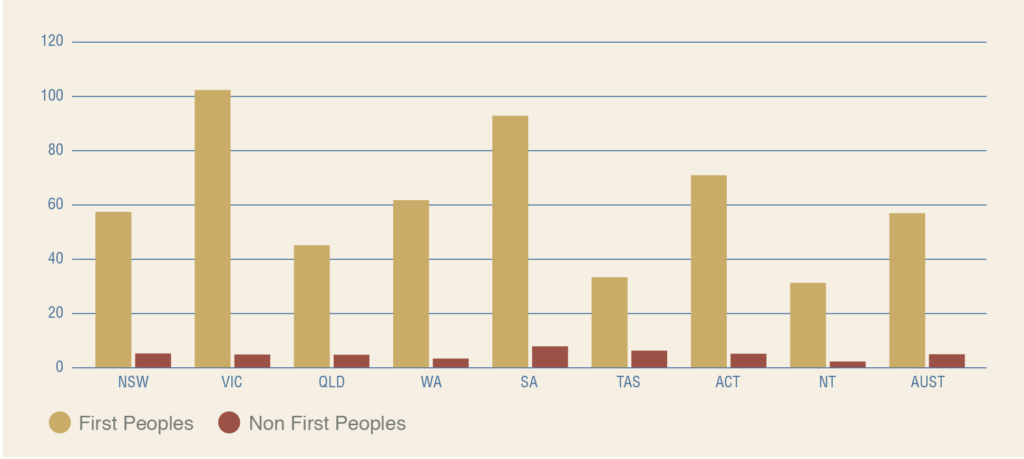

Yoorrook received evidence showing that as involvement in the child protection system intensifies from an initial report to child removal, Aboriginal children are increasingly over-represented. At 30 June 2022, when compared to non-Aboriginal children, Aboriginal children in Victoria were:

- 5.7 times as likely to be the subject of a report to child protection services

- 7.6 times as likely to have a finalised investigation by child protection services

- 8.5 times as likely to be found to be ‘in need of protection’ by child protection services

- 21.7 times as likely to be in out of home care

Yoorrook heard of ‘report fatigue’ in this area. In the last decade there have been at least 19 inquiries about the child protection system in Victoria. Recurring themes on the performance of the child protection system for First Peoples include:

- poor information gathering

- inadequate risk assessment

- lack of collaboration and information sharing between services

- poor responses to children experiencing family violence

- poor responses to children experiencing poor mental health and cumulative harm

- missed opportunities to provide early supports when receiving an unborn notification

- failures to uphold First Peoples children’s cultural rights

- lack of early support for vulnerable mothers

Yoorrook heard extensive evidence about:

- how systemic failures across multiple systems drive child protection involvement

- how discriminatory attitudes in universal services such as health can lead to unnecessary reports to child protection

- the Victorian Government not supporting First Peoples families who need help to avoid involvement in the child protection system

- the investment needed to ensure access to culturally safe and effective early help

Yoorrook was told about the urgent need to reform the way child protection authorities are notified of concerns for the welfare of unborn children. Yoorrook heard evidence of systemic racism across health services and the lack of culturally appropriate support to new mothers and how this can result in removal of their babies.

Yoorrook was told that risk assessment tools and decisions were affected by racial bias. Yoorrook further heard that many of the positive laws and policies developed to address systemic injustice in child protection were not working as intended and compliance was often poor. For example, the Victorian Government established the Aboriginal Family Led Decision Making (AFLDM) program to improve family involvement in decision-making about a child, yet in 2021–22 only 24 per cent of First Peoples children in out of home care had an AFLDM meeting. Similarly, the Aboriginal Child Specialist Advice and Support service, which promotes culturally appropriate and effective decisions around the best interests of Aboriginal children, was consulted during the investigation stage in only 63 per cent of relevant cases.

[T]he Children’s Court has not always offered a safe experience for Aboriginal children and families. Historically, trauma has precluded the full, culturally safe participation of Aboriginal families in court processes — processes that until the introduction of Marram-Ngala Ganbu were inadequately equipped to determine sensitive child protection matters in culturally welcoming, competent and safe ways.

– Ashley Morris and Magistrate Kay MacPherson

Yoorrook was told that one way to improve compliance with laws and policy was to provide free early legal help for Aboriginal families through a notification system. This would ensure families were aware of their rights and could enforce them. Evidence also highlighted the positive evaluation of Marram-Ngala Ganbu, a specialist Koori court hearing day designed around the cultural needs of Aboriginal children and families, which operates at two locations in Victoria. There were calls to expand the reach of this program statewide.

Yoorrook heard about ongoing failures in the out of home care system for First Peoples children including that:

- too many First Peoples children are still being placed with non-Aboriginal families

- too many First Peoples children are not being placed with their siblings

- there are barriers to First Peoples becoming carers in the child protection system

- there are inequities in the support provided to kinship carers (who are overwhelmingly (Aboriginal carers) and foster carers

- First Peoples children are not provided with adequate cultural plans

- First Peoples children’s health and disability needs are not being adequately assessed or met

- First Peoples children are being criminalised in residential care and the framework developed to address this is not being implemented

Yoorrook heard that once a child is removed from their family, the strict time limits for family reunification operate unfairly for Aboriginal parents, who are less likely to be able to access supports needed to address protective concerns within those timeframes.

Yoorrook heard positive evidence that when care and case management of First Peoples children is transferred to Aboriginal Community Controlled Organisations, there are better outcomes for children and families. This includes improved connection to culture and community.

Commissioner Singh speaking about culture

Yoorrook heard about the need to strengthen the legislative basis and powers of the Commissioner for Aboriginal Children and Young People to give certainty to that role and to improve oversight in the child protection and youth justice systems.

Read more about what needs to change in the child protection system in the full report.