The Past is the present

The present-day failures of Victoria’s criminal justice and child protection systems for First Peoples are deeply rooted in the colonial foundations of the State of Victoria. European invasion, and the colonial laws and policies which followed it, were predicated on beliefs of racial superiority. The systemic racism which persists today has its origins in colonial systems and institutions.

You can read more about these connections in Chapter 1 of the report.

Before European invasion, First Peoples were independent and governed by collective decision-making processes with shared kinship, language and culture. They belonged to and were custodians of defined areas of country. First Peoples were self-governing, and wielded economic and political power within their own systems of law, lore, culture, spirituality and ritual.

The purpose of colonisation was land acquisition. Theft of land was achieved by multiple strategies including destruction of culture and language and efforts to eliminate First Peoples through assimilation and violence. Colonial law was imposed on First Peoples. First Peoples were forced off their country and onto reserves and missions where their lives were controlled and cultural practices, spirituality and language suppressed. First Peoples’ children were taken.

“From the earliest stages of colonisation, colonists used violence and policing, and forcibly separated First Peoples’ children from their families. The reality for our people is that the conflict has never stopped.”

– First Peoples’ Assembly of Victoria

“The original deaths in custody have been around since 1788. It continued with the establishment of the missions. The Aboriginal people who died on those missions had no choice as to whether to be there and had no freedom of movement.”

– Uncle Johnny Lovett

Police were frequently the agents of injustice. The early criminal justice system was used to criminalise and imprison First Peoples and legitimise violence to respond to First Peoples’ resistance. While colonial law prohibited murder and rape of First Peoples, its enforcement was almost entirely absent.

The Aboriginal Protection Act 1869 (Vic) was the first legislation to explicitly authorise the making of regulations that resulted in the removal of Aboriginal children. It was followed in 1886 by amendments that became commonly known as the ‘Half-Caste Act’. Under this legislation, the Victorian Government tore Aboriginal communities and families apart to weaken collective identity and resistance, furthering the attempted erasure and elimination of First Peoples.

The Stolen Generations refers to First Peoples removed from their families as children and infants under these assimilationist laws and policies which started in 1886 and ended in around 1970. These laws and policies followed the logic of eliminating First Peoples by removing them from their families, culture and language and attempting to shape them according to European culture and values.

Police often carried out forced child removals. Until 1985 police were ‘empowered to forcibly remove children under the child welfare laws’. Justification for child removal under the various Acts was often linked to racist judgments of living conditions in Aboriginal communities.

“[As children] we were petrified of the police. They were the things passed down because of those injustices that had occurred … It was the police that were sent to remove children from their families. It still is. Police are still sent to remove. When I was a child that happened. And I’m 70. It’s still happening today. Police are being used to collect children and place them in out-of-home care — into the out-of-home system.”

– Aunty Geraldine Atkinson

Even after the explicit assimilationist intent written into child removal policies was finally removed, the administration of the laws was still infected by racial bias. The assimilationist impact continued — Aboriginal children removed from their families and siblings were placed in non-Aboriginal homes, with their Aboriginality often denied or ignored by their carers.

“When you are living in an environment that’s all non-Aboriginal, you know, you are assimilated from all of your family and your culture and your identity, you know, those assimilation processes work within the system of why they wanted to remove Aboriginal children. That’s how I see it … I honestly believed that, you know, they wanted to clear us out. Eventually there would be none of us left. I’d marry a white man and my kids would marry white people and eventually there would be none of us left. What a way to do things. ”

– Aunty Eva Jo Edwards

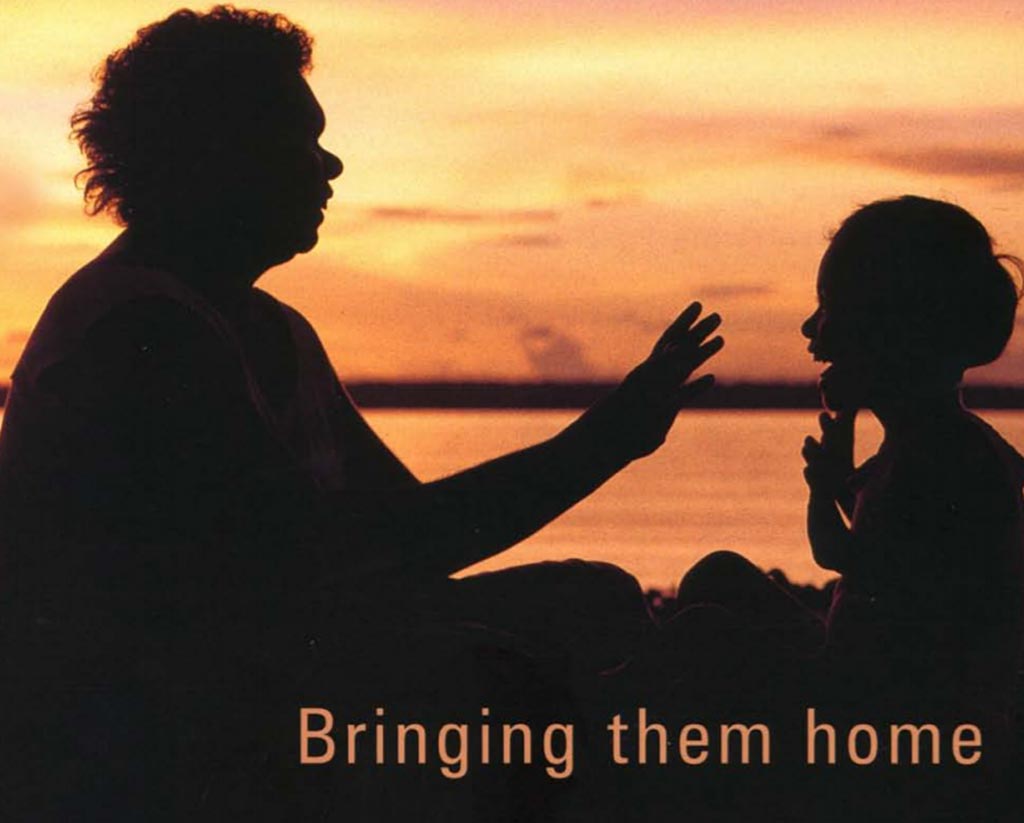

Nationally, awareness of the Stolen Generations grew following the landmark Bringing Them Home report in 1997. The report found that Australia’s forced child removal practices involved genocide under international law. Prime Minister Kevin Rudd’s Apology to Australia’s Indigenous Peoples followed in 2008.

For many non-Indigenous Australians, the forced removal of Aboriginal children from their families is considered ‘history’ and consigned to the past. For First Peoples its impact has never ceased.

The removal of Aboriginal children into white society caused immeasurable harm. Children removed from their families were traumatised, disconnected from family, culture and identity, and in many cases criminalised, experiencing homelessness, poverty, poor health and other disadvantage. Families traumatised by the loss of their children spent decades trying to reunite or simply make contact. For others, finding families was beset with obstacles, was not possible, or came too late.

“Gran was a hardworking woman — she worked numerous jobs to prove to the authorities that she was ‘fit and capable’ to look after her children. She did everything she could to try and get them back. She worked cleaning houses, trying to please white people … She wrote numerous letters requesting to live with her children, but none of these requests were ever granted. She would try and visit her children in the orphanage, but it was difficult because there was no bus to get to Ballarat.”

– The Wright Family

The trauma and harm of child removal policies has had devastating lifelong impacts. It has been passed down across generations and continues today. This history and its impacts are explained further in Chapter 1: The past is the present.

Policy Timeline

1835

Invasion and illegal settlement at present-day Melbourne, Geelong and the Bellarine Peninsula.

1836

First officials sent from Sydney to the illegal settlement at Melbourne, including bureaucrats and convicts. A police magistrate is sent from Sydney to investigate whalers’ offences against Aboriginal people at Westernport.

1836 – 1838

New settlement officially sanctioned as Port Phillip district of colony of New South Wales.

1838

Aboriginal men escaping imprisonment burn down Melbourne’s first gaol, built on Batman’s Hill.

1838 – 1849

Port Phillip Protectorate established.

1839

The Act to Allow the Aboriginal Natives of New South Wales to be Received as Competent Witnesses in Criminal Cases 1839 (NSW) sought to permit ‘every aboriginal native or any half-caste native’ to act as a witness in criminal proceedings by making an affirmation to tell the truth (rather than taking an oath). Royal Assent to this Act is refused.

1839 – 1851

Bunting Dale Aboriginal Mission, near Colac. Operated by Wesleyan Methodist Missionary Society (missionaries Hurst, Tuckfield and Oron).

1841

Merri Creek protectorate station established. Located at confluence of Merri Creek and the Yarra River. Includes Merri Creek Aboriginal School, Merri Creek Aboriginal School Dormitory, Merri Creek Aboriginal School Stockyards and Sheds.

1843

The (Colonies) Evidence Act 1843 (UK) enacted. This authorises colonial legislatures to pass laws permitting Indigenous peoples (described as ‘tribes of various barbarous and uncivilised people… destitute of the knowledge of God and of any religious belief’ and ‘incapable of giving evidence on oath’) to give unsworn evidence in criminal and civil proceedings.

1849

Port Phillip Protectorate deemed a failure and abandoned.

1851

Colony of Victoria created (separate from NSW) under Australian Constitutions Act 1850 (UK).

1853

An Act for the Regulation of the Police Force 1853 (Vic) establishes the Victoria Police Force, replacing the ‘colonial police force’ administered from NSW.

1854

An Act to amend further the Law of Evidence 1854 (Vic) provides that in any civil or criminal proceedings, evidence of ‘Aboriginal natives’ or ‘half-caste natives’ is admissible upon affirmation where the witness is ‘an uncivilised person destitute of the knowledge of God and of any fixed belief in religion or in a future state of rewards and punishments’. Replaced (with similar provisions) in 1857, 1860, 1864 and 1890.

1858 – 1859

Select Committee of the Victorian Legislative Council reviews the ‘present conditions’ of Aboriginal people and recommends reserves be established to ‘protect’ Aboriginal people from violence and disease.

1859

Ebeneezer (Lake Hindmarsh) Mission established by the Moravian Church on Wotjabaluk Country.

1860

‘Central Board Appointed to Watch over the Interests of Aborigines’ (the Board) established.

1861

Framlingham Aboriginal Reserve established by the Board and the Church of England on Kirrae Wurrung (Girai Wurrung) Country, on the Hopkins River.

1863

Lake Tyers Mission (Bung Yarnda) established by the Church of England on Gunai/Kurnai Country.

1863

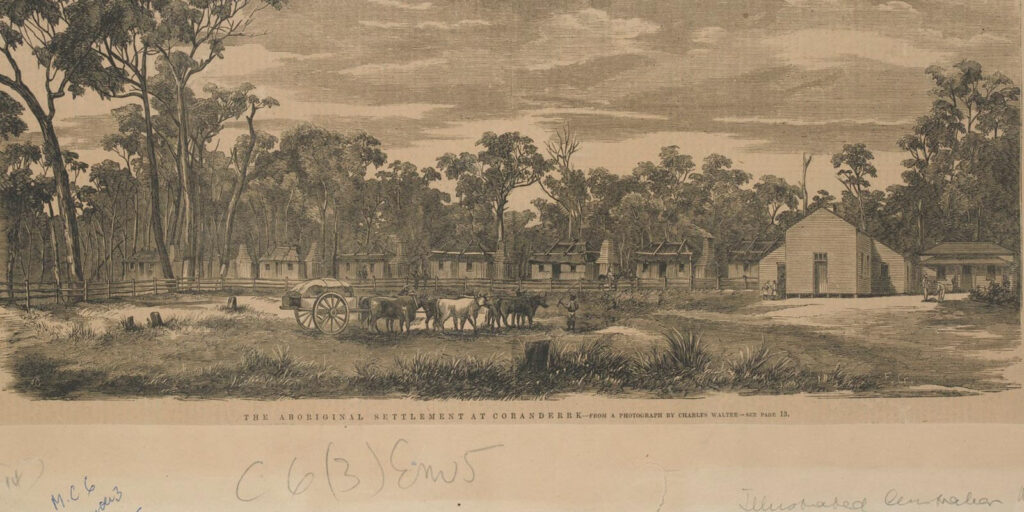

Coranderrk Aboriginal Reserve established on Woiwurrung Country, led by Kulin leaders Simon Wonga and William Barak.

1863

Ramahyuck mission established by Moravian Church on Gunai/Kurnai country, along Lake Wellington near the Avon River. Reverend Hagenauer, who established Ramahyuck mission, was one of the architects of the 1886 amendment known as the ‘Half Caste Act’.

1864

Neglected and Criminal Children’s Act 1864 (Vic) introduced. This was the first piece of Victorian legislation to define situations where children might be removed from their parents. Industrial schools for ‘neglected’ children and reformatory schools for convicted juveniles are established under the Act.

1867

Lake Condah Mission established by the Church of England on Kerrupjmara Country. It was built on the Country where the Eumerella Wars had been fought between the Gunditjmara and white settlers in the 1830s and 1840s.

1869

Aborigines Protection Act 1869 (Vic) explicitly authorises the removal of Aboriginal children. The Aborigines Protection Board replaces the Board for the Protection of the Aborigines.

1871

The Aborigines Protection Act is amended to include regulations where the Governor ‘may order the removal of any child neglected by its parents or left unprotected to any of the places of residence or to an industrial or reformatory school’.

1877

Royal Commission on the Aborigines is conducted. No Aboriginal witnesses are called.

1881

Parliamentary Coranderrk Inquiry, officially titled ‘The Board Appointed to Enquire into, and Report upon, the Present Condition and Management of the Coranderrk Station’. Kulin leaders are called to give evidence. This is ‘the only occasion in the history of nineteenth-century Victoria when an official commission was appointed to address Aboriginal peoples’ calls for land and self-determination, and one of the few times that Aboriginal witnesses were called to give evidence on matters’. However, more weight is given to the evidence given by non-Aboriginal witnesses.

1886

Aborigines Protection Act Amendment 1886 (Vic) enacted, known commonly as the ‘Half Caste Act’. As a result of this legislation, families are forcibly separated and First People of mixed descent aged between 13 and 35 (now legally classified as ‘half caste’) expelled from their communities on the missions.

1888

Cummeragunja Reserve established on Yorta Yorta/Bangerang Country, along the NSW banks of the Murray River.

1890

Aborigines Act 1890 (Vic) extends the powers of the Governor to separate Aboriginal children from their families. It grants wider regulatory powers over the living and working conditions of Aboriginal peoples, including their residence, earnings, care, custody and education of Aboriginal children, rations and medical assistance. Powers include ‘the transfer of any half-caste child, being an orphan, to the care of the department for neglected children or any institutions within Victoria for orphan children’.

1890

Licensing Act 1890 (Vic) provides that liquor must not be sold or disposed to, or to be drunk on any licensed premises by ‘any Aboriginal native at any time’.

1904

Ebeneezer (Lake Hindmarsh) Reserve closed.

1908

Ramahyuck Reserve closed.

1910

Aborigines Act 1910 (Vic) extends the power of the Board for the Protection of Aborigines by permitting them to make decisions about ‘half-caste’ Aboriginal people.

1915

Aborigines Act 1915 (Vic) consolidates previous Acts, empowering the Governor to make regulations governing the lives of Aboriginal people. Also creates offences around supplying ‘goods and chattels’ to Aboriginal people including liquor, ‘harbouring’ an Aboriginal person without permission, and assisting Aboriginal people to leave Victoria without written consent from the Minister.

1919

Lake Condah Reserve closed.

1924

Children’s Welfare Act 1924 (Vic) renames the ‘Department of Neglected Children’ to the ‘Children’s Welfare Department’.

1924

Coranderrk officially closed. All Aboriginal people remaining on stations around Victoria are moved to Lake Tyers, the only staffed institution remaining.

1928

Adoption of Children Act 1928 (Vic) provides for the transfer of parental rights, duties, obligations and liabilities to adoptive parents, and for the legitimisation of informal adoptions without the consent of both parents. This allows ‘anyone’ to arrange an adoption, and parents signing a consent form lost all rights to their child.

1939

Cummeragunja walk off. Around 200 people walk off the reserve to protest poor living conditions and management, the first Aboriginal mass protest in Australia. A strike camp is established across the river at Barmah. The strike camp lasts nine months and results in the removal of the manager. Some families return to Cummeragunja, others remain either at the Barmah Flats or the Mooroopna Flats.

1954

Children’s Welfare Act 1954 (Vic) gives the government power to ‘establish its own institutions for the care of children and for the detention of young offenders’. The Act widens the scope for judging a child as being ‘in need of care and protection’, significantly increasing the number of children sent into care.

1957

Aborigines Act 1957 (Vic) with the Aborigines Welfare Board established to administer the Act. This Board does not have the power to remove children but can instruct police to carry out removals, with the Board deciding where children should be placed under the Children’s Welfare Act 1954 (Vic).

1958

Children’s Welfare Act 1958 (Vic) expands the definition of neglect to include ‘a child living under conditions where he/she is likely to lapse into a career of vice or crime’, also extending the government’s authority and power to remove Aboriginal children. Over 10 per cent of Aboriginal children in Victoria are in State institutions.

1964

Adoption of Children Act (Vic) replaces the 1928 Act, with stricter procedures for selecting adoptive parents.

1966

Summary Offences Act 1966 (Vic) sets out a number of offences, including public intoxication.

1967

Referendum where Australians vote ‘overwhelmingly to amend the Constitution to allow the Commonwealth to make laws for Aboriginal people and include them in the census’.

1967

Aboriginal Affairs Act 1967 (Vic) gives the newly appointed Minister for Aboriginal Affairs ‘very broad powers’ emphasising housing, welfare, education and economic projects. Ministry/Director of Aboriginal Affairs, an Aboriginal Affairs Advisory Council (replacing the Aborigines Welfare Board) and Aboriginal Affairs Fund are established. For criminal proceedings, the Director can appear on behalf of an Aboriginal defendant. ‘Aborigine’ now means any person who is descended from an Aboriginal native of Australia.

1973

Victorian Aboriginal Legal Service (VALS) established. In 1975, VALS reports that ‘90 per cent of its clients involved in criminal matters had been removed from their families as children’.

1975

Racial Discrimination Act (Cth) enacted, giving effect to Australia’s obligations under the International Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Racial Discrimination. It makes it unlawful to discriminate against people on the basis of race, colour, descent or national or ethnic origin in certain areas of public life.

1976

Victorian Aboriginal Child Care Agency (VACCA) established. Its efforts combined with other Aboriginal organisations reduced the number of Aboriginal children in children’s homes by 40 per cent in three years.

1977

Equal Opportunity Act 1977 (Vic) makes it unlawful to discriminate on the basis of sex or marital status and creates the Equal Opportunity Board and Office of Equal Opportunity Commissioner (which later becomes the Victorian Equal Opportunity and Human Rights Commission). In 1995 and again in 2010, the Act expands protection from discrimination on a range of attributes, including race. ‘Race’ includes colour, descent or ancestry, nationality, ethnic background and any characteristics associated with a particular race.

1979

The Victorian Government adopts the Aboriginal Child Placement Principle which was included in the main welfare and protection laws. This stipulated that an Aboriginal family was the preferred placement for a child in out of home care.

1982

A national prison census reveals the significant over-representation of Aboriginal people in prisons around Australia. Aboriginal people in Victoria were 29 times as likely to be imprisoned than non-Indigenous people. This increased throughout the 1980s.

1984

Adoption Act 1984 (Vic) contains definitions of an ‘Aborigine’ through descent and identity; section 50 concerns adoption of an Aboriginal child.

1984

Children (Guardianship & Custody) Act 1984 (Vic) states that a Court shall not make a guardianship or custody order with respect to an Aboriginal child unless a report has been received from an Aboriginal Agency.

1988

Bicentenary ‘celebrations’ are held across Australia. Aboriginal people and supporters hold protests across Australia against the celebration of colonisation and dispossession. The largest march ever at the time was held in Sydney, with up to 100,000 peaceful protesters.

1989

Children and Young Persons Act 1989 (Vic) incorporates the Aboriginal Child Placement Principle.

2002

Victoria’s first Koori Court opens in Shepparton as a division of the Magistrates Court.

2002

Children, Youth and Families Act (Vic) makes provisions specifically relating to Aboriginal children, including the right of Aboriginal people to self-determination, Aboriginal Cultural Support Plans for children in out of home care, and ‘Aboriginal Guardianship’ which allows Aboriginal agencies to make decisions about the protection of Aboriginal children. These provisions aim to ensure Aboriginal children maintain contact with their community and culture.

2005

The first Children’s Koori Court established at the Melbourne Children’s Court.

2005

Charter of Human Rights and Responsibilities Act 2006 (Vic) enacted.

2008

Victoria’s first County Koori Court opens in Morwell.

2010

New Equal Opportunity Act 2010 (Vic).

2018

Advancing the Treaty Process with Victorians Act (Vic) commits the Victorian Government to treaty.

2019

First Peoples’ Assembly of Victoria established to advance the treaty process with the government.

2021

Yoorrook Justice Commission formally established.

2022

Victoria passes legislation (the Treaty Authority and Other Treaty Elements Bill 2022) to create the Treaty Authority to oversee treaty negotiations between the First Peoples’ Assembly of Victoria and the Victorian government, becoming the first jurisdiction in Australia to do so.

Child protection system

This section gives a high-level overview of what Yoorrook was told about the impact of Victoria’s child protection system on First Peoples.

Criminal justice system

This section gives a high-level overview of what Yoorrook was told about the impact of Victoria’s criminal justice system on First Peoples.